I was watching an interview with Michael Shannon recently where he said he enjoys acting, because it gives him a chance to behave in certain ways he’d be reprimanded for in real life. Which makes me wonder. . . do playwrights/writers create over the top, idiosyncratic characters because they also understand that socially they can’t act or get away with things certain other people do? Are characters created because of outside sources beyond our control who reacted to us in a negative way? Or does literature help writers/readers to fetishize the lower classes/less intelligent for their own entertainment, at least on the surface level? For the most part, writers steal and readers get lost in some stories when they have no claim to them. Is that really such a crime though? Do these “lower” people have the ability and resources to tell their own stories as eloquently? Do they even want to? Does writing about these people give the writer/reader a sense of superiority, or is it something more therapeutic? Kinda like ripping a Band-Aid off? Exposing the truth of the matter instead of sweeping it under the rug?

Which brings me to Tracy Letts. Letts is a double threat. He is the only person to win a Tony award for acting, and a Pulitzer Prize. While he’s probably more known for his face onscreen, we’re going to concentrate on that Pulitzer here, or at least his writing. You’ve probably seen things he’s penned too. Movie versions of August: Osage County, or Killer Joe. Killer Joe was when Matthew McConaughey was at the peak of his McConaissance. It was not, as some would like to believe, when he did Dallas Buyers Club. We were already on the downhill slide at that point.

Letts based Killer Joe in Dallas. A city he’s been vocal about hating. He’s even quoted as saying Killer Joe was “written out of anger.” Is it any wonder that he created a trailer trash thriller around the place? A small time drug dealer, Chris, wants his mother’s insurance money, hires Joe (a police detective and hit-man) to kill her, Chris can’t pay Joe, so Joe takes his sister, Dottie, as a retainer. If that’s not enough, Joe eventually discovers that the insurance money isn’t going to who he originally thought it was so he won’t be getting paid, and an affair is made public. This makes Joe furious, and what follows is a scene where a woman is forced to fellate a fried chicken drumstick.

Too much for you? Well, when this play hit the stage in the early 90’s it was too much for a lot of people. I don’t think anyone criticizing it ever stopped to think that maybe Letts wrote the play, because Dallas was too much for him. After all, he has professed that Dallas is, “the worst city in the United States.”

My “home” has been the South Texas Hill Country my entire life. I’ve never felt like I fit in here, and if reading has taught me anything it’s that I’m certainly not the only one who feels this way when it comes to the South. I’m surprised there’s not a group of us who hide in the hills and howl at the full moon in order to air out our grievances about the place. Either that or occasionally put our ears to the ground to listen for the underlying monster that likes to shape shift and present itself in forms of entitlement, addictions, racism, sexual/emotional abuse, etc.

Of course, it’s easy for black sheep to write exposing stories, isn’t it? They’re always on the outside looking in. What better way to understand the truth of the matter? The “Bastard Children of the South” as I like to call them, understand that ideas of Southern Hospitality are just a façade. A rug to cover the ugly scratch on those beautiful old hardwood floors. Even the characters in Killer Joe are courteous enough to offer beer and food to people who enter their ramshackle trailer. After all, how do you think Joe got a hold of a fried chicken leg? Who do you think it was he choked with it? That’s right, the exact same woman who offered it to him in the first place. I see what you did there Letts. Whether you meant to or not, and it’s hilarious. Making someone gag (literally) on their false niceties.

Obviously, the chicken leg scene is just an over-the-top finale to a play where Letts uses small examples of this interesting power play between what is polite and what people really are underneath their socially dictated exterior throughout the script.

Theatre critic Irving Wardle said of the morally corrupt family who hires Joe to kill, “They piously attend their victim’s funeral, hold hands for grace at dinner, and yet have a stunted response to shocking events.”

No one seems to think twice about what Joe has been hired to do, (except Chris, but by the time Chris tells Joe he no longer wants the victim dead, it’s too late. Her body’s already in a trash bag ready to be dumped) nor do they put up much of a fight when Joe takes Dottie as a retainer. Ultimately it is greed, selfishness, and big egos that drive these characters.

“It’s scary, but these people really exist. What people find unsettling about Killer Joe is that they don’t know who to align themselves with. Some people want Joe killed; others say he’s the only one with any real integrity. Chris has a vague understanding that there’s something moral out there, but he doesn’t know what it is: he’s trying to figure it out.” -Tracy Letts

Isn’t it true though? “Killer” Joe Cooper is the only character in the play who actually follows through with his promises. He says he will kill, he does. He says he wants Dottie as collateral, he takes her as such. He promises trouble if he doesn’t get paid, and he delivers. Does the fact that he killed someone, and abused a woman in the limelight for everyone to see make him less of a moral person than the trailer trash he’s been dealing with throughout the entire play who lied and cheated Joe out of his payment? Joe needs to be morally corrupt himself to fit in this story and associate with his fellow cast of characters. You need to play along in order to survive in a social situation such as the one Joe finds himself in. It doesn’t matter if the line between what he is and who hired him is blurred when it comes to moral justification. You know what that is representational of? Humanity. No one is perfectly pious. We all have our vices, suffer from anger, greed, jealousy, sadness, etc. We make mistakes, and with the social desire to sweep everything ugly about humans under the rug, we need art/literature like Killer Joe to keep us aware of what we’re doing to ourselves and to each other even if it does present itself in aggressively in-your-face forms. Hey! You probably wouldn’t have paid much attention to what the story was saying otherwise, would you? Also, “in-yer-face” is a legitimate literary term used to describe theatre exactly like what Letts writes. Honestly, nobody could’ve come up with a better one. As for the character of Chris and his moral delimma. . . Well, Chris is a little bit of all of us. All of us wading through the moral wasteland we often find ourselves in.

If I were to write a story or a play, what form would my disdain for southern living take? A wayward Texas Ranger? An angry young woman who takes a chainsaw to someone’s knees? A small town city councilman who was accused of sexual misconduct with a child, and then committed murder-suicide?

What a minute. . .

So, what happens when fact and fiction merge? Well, you get yourself a Pulitzer Prize winning play like August: Osage County. You also get something like August: Osage County when the middle class, and habits/troubles/vices of the lower class converge.

“Durant, Okla., was a town of 12,000 people, and there was a small college where my folks taught. Sometimes my family thinks I’ve made my childhood a bit more Dickensian than it was, and it probably wasn’t all that bad. But I was uncomfortable as a kid.” – Tracy Letts in a 2014 Interview

While the play takes place in a three-story household outside Pahuska, Oklahoma instead of Durant, it doesn’t much matter. A small town is a small town, and it still serves as a foundation for Letts to tell a story using pieces of his own personal history. Remember when Harper Lee refused to admit that Maycomb WAS Monroeville? Her intention in doing so was to probably let the reader come to the conclusion that the fictional town of Maycomb could be anywhere. Anywhere small and anywhere in the South. So it is with August: Osage County.

The play opens with Beverly Weston in his study/library. Beverly is the patriarch of a family of women, his 3 grown girls and wife, Violet, who is lovingly (or maybe not so much as you’ll soon discover) called Vi. In the opening of the first act Beverly is speaking to Johnna, a Cheyenne woman he has hired to care for Vi as she struggles with her declining health. Throughout this first scene, we learn that Beverly is a poet, a professor at the town college (much like Letts’s own father who even played Beverly in the Steppenwolf and Broadway productions of the play. It’s a literal family affair here), and an alcoholic. His troubles and vices are nothing compared to his wife’s though. We don’t see Vi at first. She mumbles and yells at Beverly offstage in her pill-induced, incoherent rage. She’s cancer stricken. Specifically cancer of the mouth (which turns out to be one hell of a joke). . . check out this scene with Sam Shepard from the film version of the play:

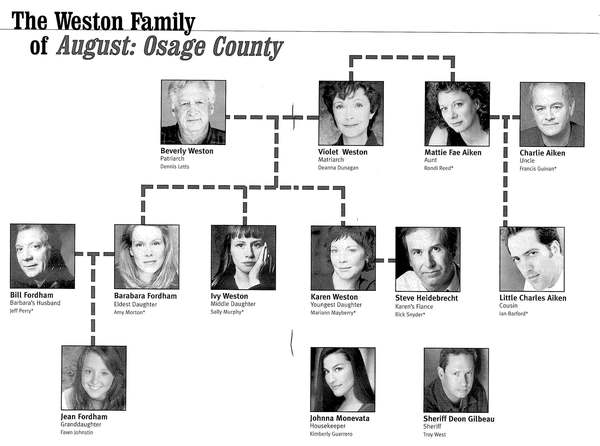

Actually. . .maybe I need to break this down for you more. There’s a lot of Westons after all. . .Here we go ’round the prickly pear, prickly pear prickly pear. . .

Beverly Weston: Patriarch of the family. Alcoholic. Poet. Professor. A prominent member of the academic community who has fallen on hard times. Although, unlike his wife, Vi, he owns up to his vices. Doesn’t try to hide them or the severity of them in the brief moments we see him, because after the opening scene, he disappears and thus begins the action of the play. Where has Beverly gone? Eventually we discover that Beverly understood that the only way out of his own personal hell was through suicide.

Violet Weston: Matriarch of the family. Violent, vile, vicious, victimizer, etc. Suffers from mouth cancer, but we’re never really sure about the severity of the issue, and her actions towards the rest of her family definitely put our empathy in check. She still smokes no matter the health risks. Takes pills like candy, because she would rather drown her sorrow with drugs than face her problems head on. She has moments of lucidity where she’s usually putting someone else in the family down to regain her dominance of the household. Emotionally abusive through and through, and cruel right down to the marrow in her bones. She rallies the rest of the family together in the Weston household during what she deems as her time of need while Beverly has gone missing. She’s big on pulling strings until she gets the sympathy she thinks she deserves whether it’s genuine or not. She has a history of abuse from her own mother we hear snippets about throughout the play. As for the mouth cancer . . .well, someone who spits vitriol as much as Vi does deserves something like that. Let’s take a look at the dinner table scene where Vi is at her worst:

This isn’t the same Vi we saw in the opening scene now, is it? These odd moments of lucidity confuse us. From that opening entrance to the dinner table we have seen plenty of what Vi is capable of. Her victimizing. Her desire for material possessions (she will not shut up about Beverly’s safety deposit box), the way she berates every one of her daughters who have come back to her in her time of need. Especially Barb, who’s cheating husband gives Vi a field day of material for insults. It’s emotional whiplash. We never know if we should show Vi some sympathy or not. This scene also shows us that despite her addiction, Vi is still in control of her family and their secrets.

Barbara Fordham neé Weston: Oldest daughter of Beverly and Violet. Vi claims she was her father’s favorite. Got out of Oklahoma and moved to Colorado, and when she did Vi claims it broke Beverly’s heart. Here we see the guilt put upon the child who wants to bust out of the coop and flee from her parents and the mediocre small town she grew up in. Does Vi’s guilt trip stem from the fact that she’s miserable in the area she’s currently inhabiting, and she wants her daughters to be miserable too? Misery loves company doesn’t it? Barbara also has one of the most memorable lines in the play:

“Hey. Please. This is not the Midwest. All right? Michigan is the Midwest, God knows why. This is the Plains: a state of mind, right, some spiritual affliction, like the Blues.”

This is not only suggestive of the impact a person’s life has on their emotions, but what an environment can do to someone as well. Barb also has a plate full of martial problems and a moody teenager she has to deal with in addition to her mother.

Bill Fordham: Barb’s husband. He’s a college professor like her father, but they’ve made a home for themselves in Colorado. Bill’s cheating on her with one of his students, and he’s a symbol of mistakes that can be overcome. He tells Barb:

“You’re thoughtful, Barbara, but you’re not open. You’re passionate, but you’re hard. You’re a good, decent, funny, wonderful woman, and I love you, but you’re a pain in the ass.”

Barbara is a pain in the ass, and she needs to hear it. She’s somewhat inadvertently followed in her mother’s footsteps. It wasn’t enough for her to move away from her hometown and her mother’s abusive nature. The venom her mother spewed infected her anyway, and we see evidence of that when she back-hands Jean for mouthing off later in the play.

Jean Fordham: Barbara’s daughter. At only 14 she’s a constant reminder of the abusive cycle that has plagued Vi, Barbara and her sisters, and now young Jean. You can chalk up Jean’s aloofness and disinterest about he entire situation to the fact that she’s still just a child, but Jean’s youth is interesting here. She’s young and unmolded by the abuse her mother endured growing up. Therefore, she stands as a moral compass in the claustrophobic atmosphere her grandmother has created in the household whether she wants to be one or not. Jean’s young age and naïveté represents an ideal black and white sense of right and wrong that does not exist in the adult world. In retaliation Jean seeks solitude from this mess she’s been dragged into. She smokes pot, and disassociates especially when it comes to the death of her grandfather. Why should she show her respects to a man who did nothing to salvage the ruins of his family and found suicide to be the only way he could finally be set free?

Ivy Weston: Middle daughter. Remained in her hometown to take care of Vi. Works at the university her father taught at. Usually the first one to receive Vi’s verbal assaults. In her 40’s. Never married mostly due to a lack of any real prospective partners where she resides. This causes a bigger problem than you can possibly imagine later on in the play, and Vi incessantly ribs her about it. Vi even goes so far as to tell Ivy that she looks like a lesbian with the way she wears her hair.

Karen Weston: Youngest daughter. Hopeless romantic. When her new fiancé tries to sexually abuse Jean, she claims it was the poor teenager’s own fault. She absolutely refuses to see the ugliness in a situation. Wants to live her life in a better, kinder atmosphere than the rest. A defense mechanism and a form of disassociating on her part. Karen can’t handle the truth even when it’s right in front of her own eyes. She chooses to remain with her predatory fiancé in order to escape an even worse hell by remaining alone with her family. At one point Karen admits to applauding her own parents for sticking together in their marriage for so long, but it is quickly brought to her attention that her father literally killed himself to get out of it, and yet she chooses to overlook that fact. She is more concerned with planning her own wedding than the state of her mother’s mental and physical health or even the death of her father. It mirrors Vi and her obsession with the safety deposit box. Like selfish mother like selfish daughter.

Steve Heidebrecht: Karen’s fiancé. Has been married three times prior. A womanizer and sexual assaulter. Representative of Karen’s negative coping mechanisms and fear of being alone. She’d rather be with someone who’s morally corrupt than deal with her problems on her own. At least Steve isn’t as bad as her mother.

Mattie Fae Aiken: Vi’s sister. Growing up, she endured the same abuse Vi did. While Mattie Fae doesn’t seem as cruel as Vi at first we discover that she has her own unhealthy coping mechanisms that stem from regret, self-loathing, and disappointment. Her son, Little Charles, bears the brunt of this as he’s constantly chided for the smallest things. She sees him as a constant reminder of her failures as a person and as a mother.

Charlie Aiken: Mattie Fae’s husband. He is the only elder member of the family who is kind and compassionate towards Little Charles. While Charlie is more minor than the other characters in the play he has some of the most telling lines. In regards to how Mattie Fae treats their son he constantly reminds her, “That’s your son, Mattie Fae.” Little Charles is her son, but why is her husband not taking any claim to him?

Little Charles Aiken: If it wasn’t bad enough to be called “Little”! Poor Little Charles is representative of the fact that abuse does not discriminate between the sexes. He gets just as much cruelty thrown his way as Vi’s daughters do. While Little Charles is in fact Mattie Fae’s son, he has no connection to Charlie other than the fact that they share a name. Little Charles is actually Beverly’s son. Mattie Fae made a mistake, and paid for it for the rest of her life. To put the icing on top, remember when I said Ivy’s lack of romantic partners would prove to be a big problem? Well, just guess who she loves and wants to run away to New York City with. . .Little Charles. Small town women always want to run away to bigger cities, how stereotypical. Ha! Ivy and Little Charles are fully aware that they’re cousins, or at least that’s what they’ve obviously been lead to believe. Finding out that they’re half siblings would ruin them. Barbara discovers this secret and is thus given the hard task of breaking the news. Mattie Fae certainly won’t own up to it. However, the Weston family’s actions towards one another are so vile that Barb thinks for a moment that maybe a genuine loving connection between two of its members wouldn’t be the worst thing in the world. She argues a case for incest by saying, “it’s not that uncommon.” However, Ivy seeking a romance with Little Charles further entraps her in the mess her family has created out of their selfishness, abuse, and lies.

Johnna Monevata: Vi’s live in caretaker. A Cheyanne woman who was seeking a respectable job. Beverly hired her to take care of Vi and her drug problem after he was gone. Vi refers to her as “The Indian in the Attic”, because that’s where she resides on the outskirts of the family as a willing outcast. Besides, what is the South without some blatant racism?

Sheriff Deon Gilbeau: Barb’s prom date from high school who is now the sheriff in town, and found Beverly’s body. A drowning that was determined a suicide. He’s a reminder of what could have been had Barb stayed in Pahuska. Not that it would’ve been much better from what she found when she left.

By the end of the play the Weston family’s secrets are revealed. Ivy finds out the truth about Little Charles, but not from the mouth of Barb. Vi knew all along. At the end of the play Vi’s filter is shot by the pills, and she lets it slip. Vi also admits that she knew Beverly planned to kill himself. He had left a note. Why do you think she was so worried about that safety deposit box? Of course, Vi doesn’t want to be the only individual responsible for Beverly’s death, so she once again mentions that Barb’s “abandonment” by moving away is what killed him. She yells at Barb, “Nobody is stronger than me, goddamn it. When nothing is left, when everything is gone and disappeared, I’ll be here. Who’s stronger now, you son-of-a-bitch?” At this Barb leaves Vi to fend for herself with only Johnna for company. Selfishness, narcissism, lying, secrets, and emotional turmoil have destroyed this family.

Bless your heart, Vi.

Bless. Your. Heart. But ultimately you did this to yourself. A trickle down effect involving emotional abuse that’s left you alone with a woman who is only there for you, because of the job requirements. That “Indian in the Attic.” That Southern Hospitality won’t help you now. You were never hospitable in the first place. That sympathy you wanted so badly, and worked so cruelly to get wasn’t deserved.

And that’s the way the world ends. . .

Is the Weston Family just one small example of life in the South where human behavior gets out of hand? No, but I’ll tell you what the Weston Family is. It’s a microcosm. An ugly, slightly over-the-top to some, representation of small southern communities at large. The Weston family is nearly big enough to be it’s own tiny community after all. Vi represents the failure of people in power in the older generations, Barb and her sisters represent those who tried and failed to change things, and Jean, the youngest of them all, represents the youth of the community who are expected to learn right from wrong as if it were as clear as black or white from people who have such an ugly duality about them coupled with incredibly loose morals and emotional baggage.

Of course, Tracy Letts isn’t on his own here when it comes to exposing the cultural incongruities of the South. . .

So what/who are “The Bastard Children of the South?” Letts is one for sure, but what about other writers? Lets take a look at Joan Didion. While she isn’t from the South, she got close enough to it to have her own opinion, “It occurred to me almost constantly in the South that had I lived there I would have been an eccentric and full of anger, and I wondered what form the anger would have taken. Would I have taken up causes, or would I have simply knifed somebody?” – Joan Didion from South and West

Don’t you see Joan, our beloved Lady of Existential Dread? Just by writing about the South you’re committing your own small act of violence against it. Exposing it to the truth. A truth that stems from the anger you feel towards what the South is for you. Welcome, our honorary Bastard Child! Guess stealing stories from the lower classes, and writing about them is, above all, a therapeutic endeavor.

After all, there’s a whole slew of southern writers who have taken their environment, and molded it into exposing stories:

Harper Lee’s Love/Hate Relationship with Her Hometown.

David Sedaris and “The Rooster”.

There’s an entire literary magazine dedicated to breaking down Southern stereotypes and ways of living that have been thrust upon those of us who grew up there, and have a desire to see some change. Good luck you pioneers! The South will not change in our lifetime, and before we know it the younger generations might grow up and find there’s nothing in the South worth salvaging.

Even Tracy’s own mother, Billie Letts, couldn’t resist picking up a pen and writing something down.

I guess what I’m trying really to say here is don’t blame the writer when you can’t handle a variation of the truth. What’s ugly about humans is often the most truthful, and if that comes from hard to swallow stories, so be it. Someone’s gotta tell them. We gotta humiliate those who deserve it even if it’s in an artistic form that will most likely never be experienced by those it’s about. What does that matter though? It’s not FOR them. It’s for the rest of us. Those of us that find ourselves on the outskirts of everything. Who can see what’s wrong with the big picture. Who know that small towns aren’t pleasant and quaint. Instead, simply put, they’re their own little shit shows.

“. . . some spiritual affliction. . .”

[…] that blinds people in this town. There’s a lack of “Southern Hospitality” (I talk about how I think it’s all just a big ol’ myth in this post), it’s hard to find common interests and form relationships, especially for the younger […]

LikeLike

[…] Click here to read my two cents on “Southern Hospitality” from 2019 […]

LikeLike