This list is in no particular order. . .

1. Homesick for Another World by Ottessa Moshfegh: When I was younger, and a little more angsty, I enjoyed reading stories that shocked me, made me uncomfortable, opened me up and then put me back a little incorrectly. Then life got a hold of me. I started experiencing things more fully on my own. I became too sensitive. I no longer wanted to read stories that mirrored or even leapt past my own negative experiences. I read Moshfegh’s Eileen a few years ago. I made it through the novel, but didn’t love it as much as everyone else. It seemed to reach into the dark recesses of my mind and dig up things I didn’t want exposed to too much thought. Last year I tried Moshfegh again with My Year of Rest and Relaxation, and discovered that once again it felt good to read something that slapped me with some of that negativity and edginess I loved in literature before. I guess I felt comfortable letting my thoughts wander over to the darker side of things once again. I think it’s safe to say that Moshfegh has finally reeled me in. All of the stories in this collection are uncomfortable in one way or another. Whether it deals with drugs, sexuality, murder, lies, depression, mysticality, biology, etc. All of the ugly aspects of life are fair game, and Moshfegh utilizes them so eloquently that you’re simultaneously subtly shocked and awed that someone hasn’t exposed the repulsiveness of humanity quite like this before.

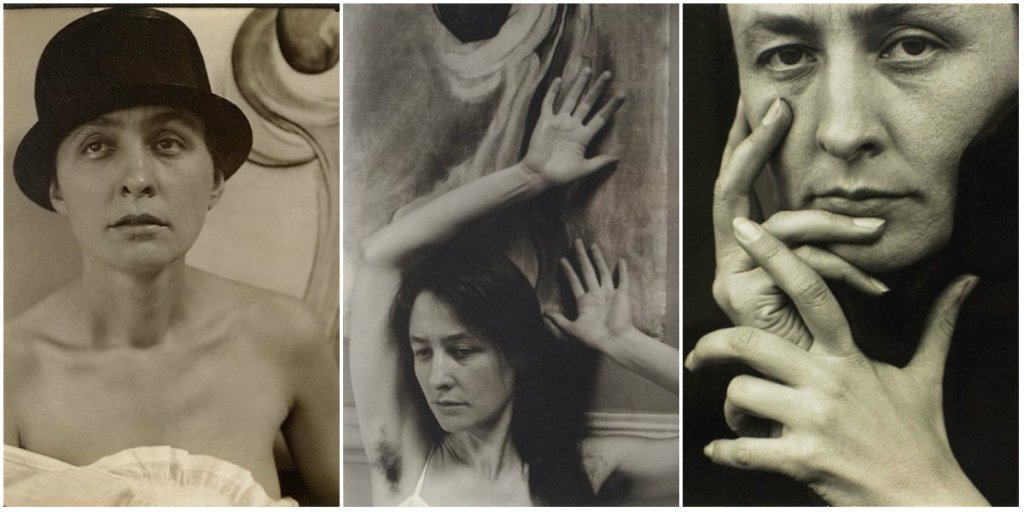

2. Portrait of an Artist: A Biography of Georgia O’Keeffe by Laurie Lisle: Well researched, thorough, and published while O’Keeffe was still alive. While perhaps not the best written biography, it is one of the only comprehensive biographies on the artist, and the author did have access to a lot of individuals who knew O’Keeffe personally at different moments in her lifetime. What Lisle did with those interviews was paint a deeper picture of O’Keeffe for the reader. We’re all familiar with the Steiglitz photographs. . .

Those dark eyes, sharp jawline, and long fingers. . .but that’s just the surface. Perhaps if you look closer you can see the determined, introverted, and fiercely independent woman who painted what she wanted in the midst of a medium that was mostly full of men. She painted beautiful southwest landscapes, skulls, and of course those famous flowers. She even dabbled in a little sculpture at the end of her life. Those yonic flowers though? Not so yonic when you take away the Freudian theory that art critics thrust upon them. Georgia was a little more simpler than that, and was known to hate such theories whether in reference to psychology or her artwork. She was driven by what she found beautiful and how it made her feel, and she found words and descriptions of her work unnecessary. Knowing that, it’s almost funny that she let the story of her life be penned.

3. A Ladder to the Sky by John Boyne: Many have said that their expectations for this novel where high after reading John Boyne’s 2017 masterpiece, The Heart’s Invisible Furies. I am no exception. While this novel didn’t quite live up to the standards that Invisible Furies set for me, I still thoroughly enjoyed it. Boyne, who is a self professed John Irving fan, seems to have taken a page from that renowned American novelist’s book. I love Irving’s novels, so that just made reading this a treat. In A Ladder to the Sky we follow Maurice Swift through his early twenties to old age, and all the sexual exploits and nastiness in between. A handsome manipulator, Swift is determined to sleep with and gaslight his way through any man or woman who can help him achieve his dream of becoming an award winning novelist. There’s a couple of problems though. Swift doesn’t seem to have any natural writing talent, and no imagination whatsoever. This is a dark satire if ever there was one of the publishing world and some of the writers who inhabit it.

4. Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking by Susan Cain: I distinctly remember in college a certain professor made going to class torture for me the first semester of my senior year. This professor would single me out and call on me first nearly every day, she’d tell me to speak up and say she couldn’t hear when I knew perfectly well she could as I was sitting in the front of the class, the last straw was the day she had us watch a video and told us to take notes. While I was soaking in the information of the first few minutes of the video she flashed the classroom lights back on, looked me straight in the eye, and made like she was addressing the whole class (yet was singling me out because she did not break eye contact with me while I could feel my cheeks turn red at her sudden outburst) and nearly yelled that we were supposed to be taking notes, not just sitting there. It was so bad, and I finally came to the conclusion that she would never stop picking on me or singling me out for every move I made. She could do this because I went to a tiny, private, liberal arts school. Perhaps she thought “tough love” would help give me more confidence and magically make me more outgoing, but it had the reverse effect. I realized that I couldn’t learn anything from her when my nerves were on edge every time I set foot in the classroom, and I absolutely did not find her approachable as a teacher. I stopped going to class about 3 weeks in, and chose not to talk to anyone to try and drop it. I was done. I’d take the F and leave it at that. Well, that F put me on academic probation which required meetings. I hated those too. The student liaison I had to meet with wasn’t much older than I was, and yet she still didn’t understand the personality clashes I had to deal with as an introverted student. When I tried to explain my feelings and situations I often found myself in she discovered that I was much more informed than her on the topic, and that made her feel threatened. Possibly, she was having a hard time trying to figure out how to help me. However, she became arrogant in order not to lose her authority, and I eventually stopped going to the meetings as well. Thankfully, the first meeting was the only one that was required. Susan Cain wonderfully explains how in a world where the extrovert is the ideal personality, introverts are often looked over, our intelligence and talents are wasted, and our authenticity is put in jeopardy as we try to become more of an extrovert to fit in with what society desires in world leaders, bosses, students, friends, parents, children, etc. This book does not villainize extroverts. Cain merely sets up and explains in depth the differences between the two personality types for us, and gives the introverts a fighting chance for once. I think this is mandatory reading, especially if you are a teacher. I can’t imagine much has changed in the relationships they have with introverted students since my own time in school. Lack of knowledge in personality differences is hindering, and at times destructive to learning. Take that on authority from your local neighborhood shy introvert, who took more than 4 years to graduate college.

4. After the Quake by Haruki Murakami: A book of 6 short stories that don’t necessarily revolve around the 1995 Kobe earthquake but feature it in one aspect or another even if it’s just in passing. It’s been a minute since I read some Murakami, and this was a delight. Surreal, slightly heartbreaking, and oddly funny in some places. What better way to get through the wake of a disaster, natural or man made, than by an attack on reality through storytelling.

5. Into the Wild by Jon Krakauer: Let’s be honest. When Chris “Alexander Supertramp” McCandless set out to live in the Alaska wilderness for a few months in 1992 he was ill prepared, naïve, over ambitious, and some might even say mentally unstable. What really killed him though, at least to me, wasn’t the starvation that came from being unprepared, but an unreachable idealism. He went “into the wild” to escape the confines of civilization. After all, he managed to hitchhike and tramp around the Western United States with a 5lb bag of rice, some freshly caught fish, and little else before he set off for Alaska. If he could manage that, he seemed to think he could manage much more. He wanted to explore “uncharted territory” and come out on the other side a changed man. In pursuing this, he threw out his map of the Alaskan frontier, which was arguably his greatest downfall. He was so close to survival, and didn’t even know it. There were cabins, and a ranger station close by his camp at Bus 142 that he might’ve been able to reach even in his emaciated state, but without the map he had no idea. McCandless seemed to be running from disappointment. Especially the disappointment that stems from the hypocrisy and multifaceted aspects that come from being human. One of the most controversial things about this book is whether Chris is a hero or a moron. Whether this is a tale of an heroic undertaking that went terribly wrong, or a tale of caution. This book has you asking all sorts of questions associated with these ideas, and makes you look long and hard at the duplexity of your own life.

6. On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous by Ocean Vuong: The best piece of fiction I read in 2020 belongs to this beautiful little novel. Narrated by “Little Dog” in the form of a letter to his illiterate, immigrant mother. In his mother not being able to read, “Little Dog” allows himself to be more open, and implacable in his truth. He states, “The impossibility of you reading this makes my telling it possible.” Set in Connecticut in a predominantly white community, we explore the life of a first generation Vietnamese-American as he struggles to assimilate into society, as well has hold onto his heritage. This novel also touches on the horrors of war, abusive parents, drug addiction (particularly the opioid epidemic), mental illness, and sexuality. While such heavy themes have the potential to bog down a story (lookin’ at you Shuggie Bain! I mean I did enjoy the 2020 Man Booker Prize winner as a whole, but it was certainly very tough to get through at times). In contrast to Shuggie’s author Douglas Stuart, Vuong manages to alleviate some of those hard hitting themes with his flowery language. While I don’t always like when poets write prose, Vuong is masterful here in his first novel, and has quite a grasp on his literary voice. “A page, turning, is a wing lifted with no twin, and therefore no flight. And yet we are moved.” And boy was I moved.

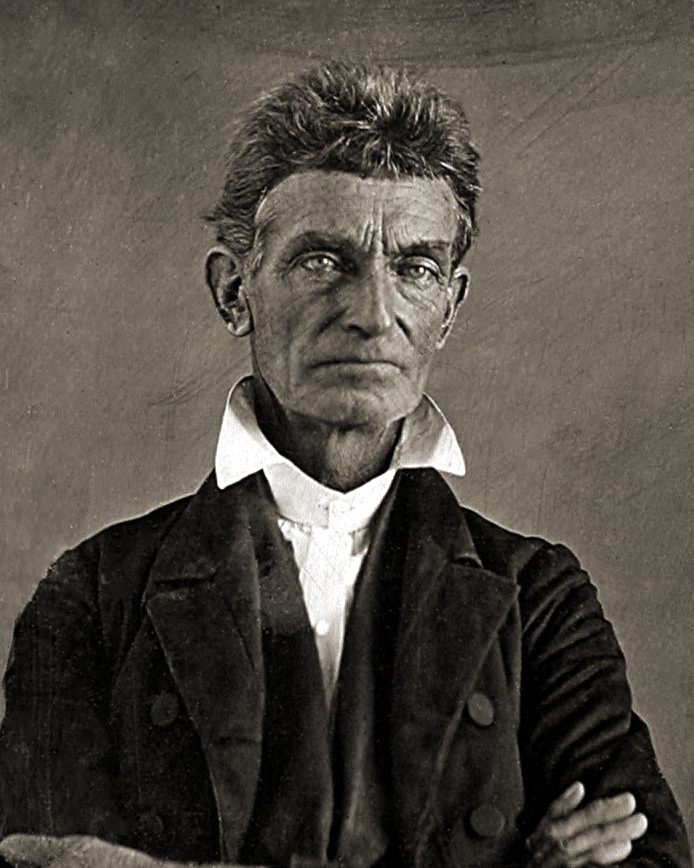

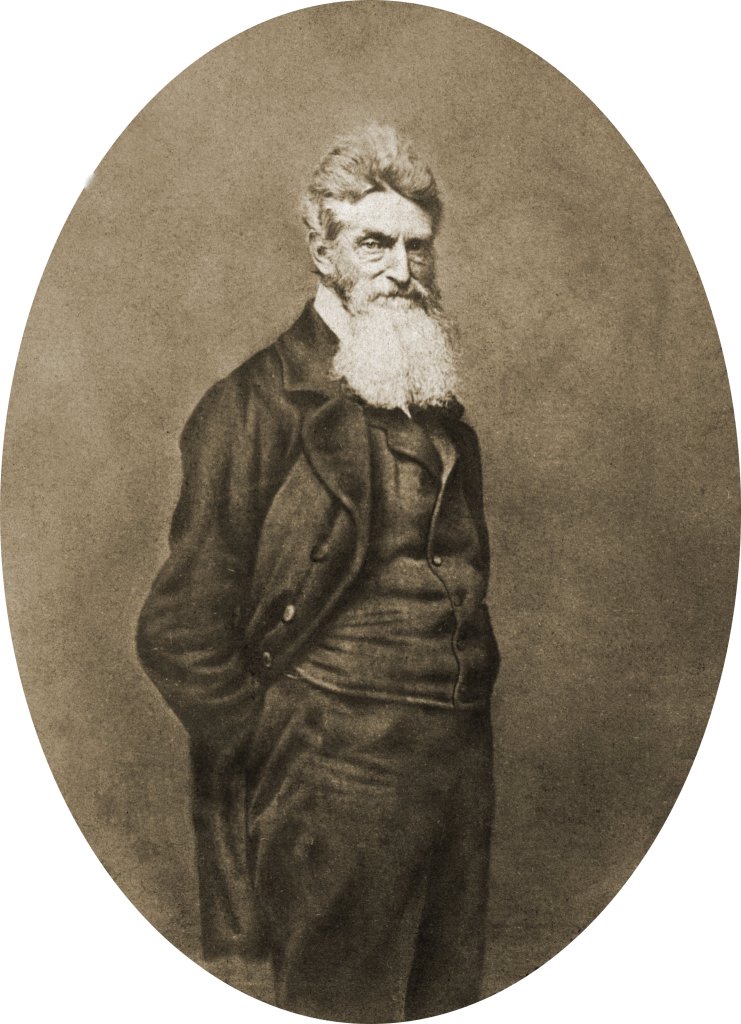

Right: John Brown in 1859

7. The Good Lord Bird by James McBride: John Brown. . . that fiery, God loving, gun toting, abolitionist who attacked Harper’s Ferry with a small band of men, and was the first person ever to be executed for treason in the United States usually just ends up as a footnote in history books finally gets his due, albeit a fictional one. How fitting though, for a man who seemed made up of the mythical. I picked this up, because James McBride’s most recent novel, Deacon King Kong, was all over my Goodreads feed in 2020. When I finally clicked on the link to his author page, I realized that this 2013 McBride novel had been on my To Read List for a while. I got the message the universe was trying to send me, and dove into this wonderfully narrated novel. “Onion” a boy who’s found himself dressed as a girl and mixed up with old Osawatomie John Brown’s gang tells this story. It’s a fast paced, epic tale of a man determined in his beliefs and in helping to right the sins of the world. Also, it’s FUNNY. I don’t know who they’re calling the 21st century’s Mark Twain these days, but James McBride is a good candidate for it. I’ll surely be reading more of what he has to offer. Side Note: If you’re interested in watching Showtime’s miniseries based on the book starring Ethan Hawke and Joshua Caleb Johnson I recommend it.

8. Sharks in the Time of Saviors by Kawai Strong Washburn: When I finished Kawai Strong Washburn’s debut novel, I thought it was a great contender for the 2020 Man Booker Prize List. Sadly, I was mistaken. No matter! It was still an engrossing and wonderful read. A family saga that integrates Hawaiian folklore and magical realism. It explores what it means to be a native Hawaiian, the issues natives face on the islands and the mainland, and the idea that we all have something to offer in our lifetimes, whether it’s immediately apparent or not, and how sometimes we need to enlist the help of our traditions and ancestors to figure it all out. While reading this I realized that pretty much everything I know about Hawaiian history and its culture came from Sarah Vowell, and that is not sufficient enough. I found that I had to look up Hawaiian slang terms and pidgen phrases throughout reading this, but that just made the experience even more engaging.

9. Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland by Patrick Radden Keefe: So nice, I read it twice! Say Nothing tells the story of “The Troubles” from 1968 to pretty much the present day (because has the fight really ended?) with the help of two women on different sides of the conflict. The first is Jean McConville. A Protestant woman who married a Catholic man in the 1950’s when “mixed marriages” weren’t so frowned upon, and had 10 children. When her husband died of cancer in the early 70’s, Jean was left to take care of the children on her own in the midst of guerrilla warfare. She was kidnapped by the IRA and “disappeared” in 1972 leaving her children to fend for themselves until the state finally intervened months later, and they were separated. Her body was not recovered until 2003. They say she was a “tout”, an informer for the British forces in Ireland, but others believe that her only crimes were being a Protestant (although she became a Catholic after marrying), and helping a wounded British soldier outside her apartment in Divis Flats one night.

The second woman is Dolours Price. As a young woman in 1969, she participated in a peaceful march that would make its way from Belfast to Derry, and was mirrored after the Selma to Montgomery March in the United States which took place in 1965. Much like the march in Alabama, things quickly turned violent for Dolours and her fellow peaceful protesters. They were attacked by a crowd of Ulster Loyalists at Burntollet Bridge near Derry. At that time in Ireland, the struggle was very sectarian. The Protestants who were mostly loyal to the British Crown were favored over the Catholics who wanted a united and free Ireland out from under British rule. Catholics were heavily discriminated against. They were passed over for jobs they were completely qualified for, as well as public housing, and schools were segregated. Many believe that the attack on Burntollet Bridge is what sparked the Troubles in the first place. This incident eventually lead to more violence, most notably The Battle of the Bogside. The British Army was soon deployed a few days after the Bogside riots erupted to restore some peace and order. They claimed that the situation was ” being deliberately exploited by the IRA and other extremists”. This did not go over well with the Catholic population in the area, and their relationship with the British Army quickly deteriorated. (Gee, doesn’t military action during moments of civil unrest, and rioting sound eerily familiar?)

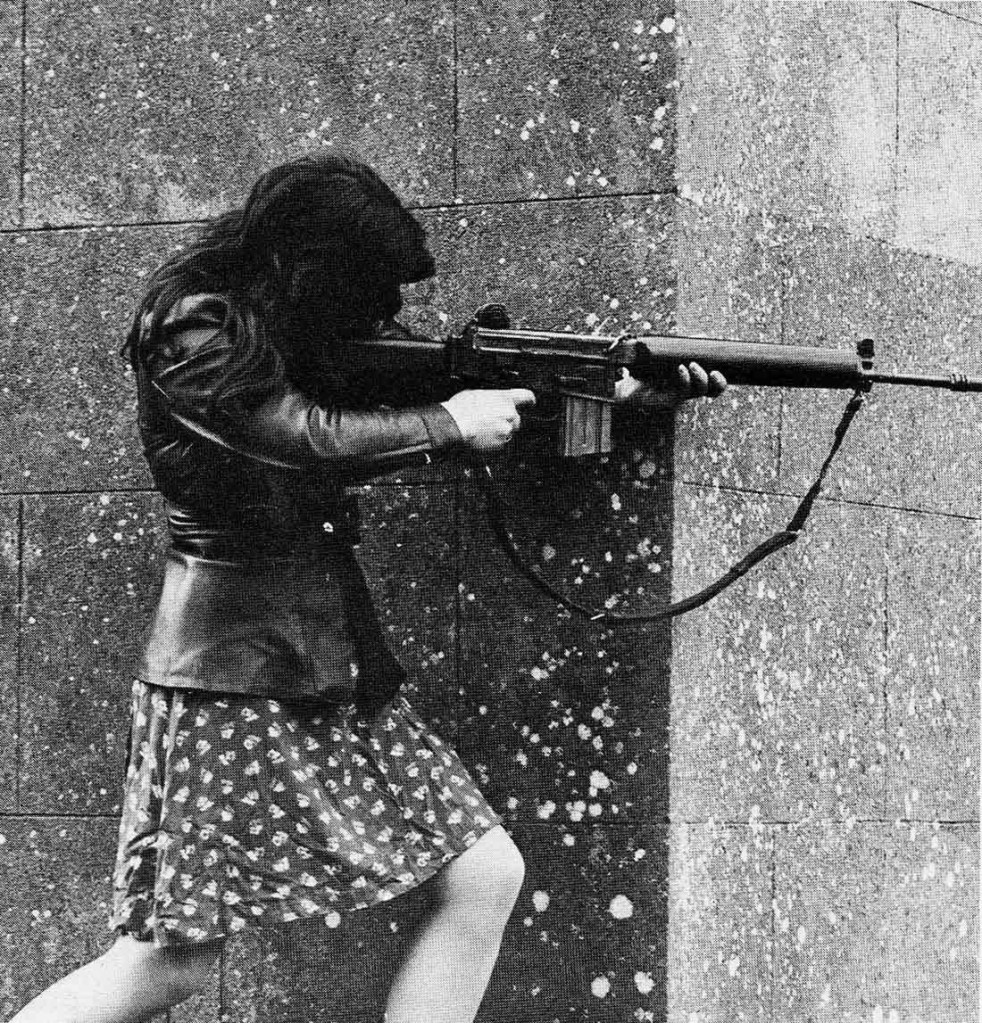

While Dolours grew up in a very Irish Republican household, it wasn’t until the violence that she witnessed during the march that made it clear to her that peaceful protest was not the answer. She originally believed that the armed struggle did not work. Her parents had used such tactics in their fight to join the Republic, and they had nothing to show for it. Soon, she became radicalized, and joined the Provisional IRA (not to be confused with the Official IRA who were not well armed to defend the Catholic neighborhoods in the North and had renounced violence. They eventually fell to the wayside over the next few decades). Dolours was one of the first women to find herself involved in the Provos , instead of the women’s branch of the paramilitary group, Cumann na mBan, claiming that she did not want to be ordered to simply make tea and roll bandages. In 1973, along with her sister Marian, Dolours participated in the car bombing of the Old Bailey in London. Due to an informer somewhere in the ranks of the IRA back home, the sisters were caught and jailed in England where they began a hunger strike years before Bobby Sands would in 1981. Both Dolours and Marian survived due to being force fed (for nearly 170 days), but their hunger strike worked along with a truce to ceasefire by the IRA (which didn’t last long). They wished to be returned to Ireland so they could finish out their sentences as prisoners of war, which they did in the Armagh Gaol. However, Dolours didn’t completely escape the after effects of her strike. She had a prolonged issue with eating throughout the rest of her life, and suffered from anorexia. Her time in jail also made her rethink her radical actions as well as her hand in killing innocent people. She, in fact, had driven Jean McConville to her execution along with many other “disappeareds” throughout the 1970’s as a member of the Unknowns. If you’re unsure whether to believe in her regret for the people she helped kill during this time, look no further than the documentary I, Dolours.

Dolours and Marian’s imprisonment received a lot of media attention in England at the time. The Daily Mirror remarked that, “the legend that women were passive aggressive, peace-loving creatures who want only to stay at home and look after children has been finally exploded in a thunder of bombs and bullets.” They even accused feminism of radicalizing these young women. HA! Although, looking at the photos below, the Price Sisters really did set a new, hip standard for “revolutionary chic”.

Dolours spent the majority of her twenties in incarceration. She only served 7 years of her life sentence and was released in 1980 on humanitarian grounds. If Dolours’s life wasn’t interesting enough for you already, she married renowned Irish actor, Stephen Rea, in 1983. The marriage lasted 20 years, and the couple had 2 sons.

I read this book, because my knowledge of the Troubles was close to none. Bloody Sunday was just something mentioned as a footnote in high school history classes, if at all. I knew Bobby Sands was a hunger striker, but I didn’t know that he was just one of many, because Ireland has a very long history of hunger strikes. I learned that the British refused to call the Troubles a war, but were quick to define the IRA as a terrorist group. In the instances that the Troubles became very sectarian, it’s hard to understand if the fighting was about religion, or Irish freedom. For instance, when you look up the causalities of a bombing, they usually have the victims separated into their different religious sects as late as 1998. Keefe does a fine job of deconstructing, and explaining the who’s, what’s, and why’s of the Troubles. He uses both Jean McConville and Dolours Price as springboards to give some humanity to those fighting during the Troubles, and those who weren’t, because when you get right down to it, it is a fight for everyone. No matter if you’re a member of an organization or not, civilians are not immune to war-like conflict. If it wasn’t for the Belfast Project at Boston College, and Ed Maloney & Anthony McIntyre’s desire to preserve history, Keefe wouldn’t have been able to tell this story like he did. The tapes were not to be released until the death of the individuals interviewed, since many belonged to the IRA and the repercussions of talking about their involvement are still a threat to this day. However, that did not pan out. When Dolours Price confided in an interview that (now former) Sinn Fein president, Gerry Adams, was the IRA commanding officer who ordered the killing of Jean McConville, it set off a series of events that threatened to muddy the claims that Adams had made that the IRA affiliated political party was strictly committed to peaceful politics.

Another Fun Fact: In 2018, Gerry Adams had a Negotiator’s Cookbook published to push the peace envelope even further. They’ve labeled it as the “best kept secret of the Irish peace process.” What a way to tout your image Gerry, and. . . wait for it. . . give peas a chance!

Keefe even took the title of this book, Say Nothing, from a Seamus Heaney poem that deals with the intimidation tactics of the military and paramilitaries in Ireland to ensure that people kept their mouths shut, and to withstand the interrogation of the British army. While most believe that the Troubles ended in 1998 with a ceasefire and the Good Friday Agreement, the IRA formally stopped their armed campaign in 2005, and there are still dissident groups of the IRA active to this day. Violence is sporadic, but the most recent attack on British Troops happened in 2019, and involved the accidental killing of Belfast-born journalist, Lyra McKee. The other Price sister, Marian, has continued to be involved in the conflict as recent at 2009. She was involved in an attack on a British Army Barracks where two soldiers were killed, and eventually released from jail in 2013. This attack was orchestrated by the Real IRA, a splinter group formed by members of the Provos. Dolours died of an accidental drug overdose that same year.

This book sent me down a rabbit hole, and gave me a hunger for more information on the Troubles. I read more than just Say Nothing in 2020, not because I found it lacking, but because I wanted to know more about this war that’s been raging in the backyard of a civilized society for years. While I did enjoy the other books I read, Say Nothing gives the reader a blanket of information that’s needed to delve deeper into the Troubles. Perhaps Keefe knew exactly what he was doing when he wrote this, and wanted his readers to continue learning long after his book was finished. I could go on and on about the Troubles, and just might do so in another post at some point later this year. I’ve said too much here already, but can you really blame me? It opened me up to a whole new world I didn’t know I had such a craving to know more about!

10. American Gods by Neil Gaiman: This was not my first Gaiman, but it is by far the best I’ve read so far. I’m not a huge fan of fantasy novels, but I do have to admit that some are a joy to read. Uniquely American in that roadside attractions are a common setting throughout the novel, and in the old gods that populate this book we see and understand America as the melting pot it is. As I wade through Gaiman’s bibliography, I’ve got a theory that perhaps he’s never really been at the top of his game unless Terry Prachett has had at least one finger in the writing process. Gaiman has stated that he has a fondness for collaboration, and that he consulted Prachett on some plot points for American Gods. While I haven’t read Good Omens, I did enjoy the Amazon Prime series. On another note, I should probably read some Prachett in 2021 since I never have before. . .

11. The Butcher Boy by Patrick McCabe: This novel is narrated by our protagonist, Francis (Francie) Brady, a poor underdog living in a small Irish town with an emotionally unwell mother, and a drunk bastard of a father. When Francie breaks into a more well-to-do neighbor’s home who called his family “pigs”, it all goes further downhill for him. He’s taken to a home for delinquent boys where he’s molested by a priest, returns home to find he’s lost his friendship with the only boy in town he could ever really stand, and he drops out of school to become a butcher’s apprentice. The butchering will come in handy for Francis later in the novel in a more grisly way. . . let’s just say that Cormac McCarthy wasn’t the first to have his character use a captive bolt stunner pistol as his weapon of choice. Throughout all of this we find that Francie is gradually losing his mind. The line between reality and delusion is heavily blurred. McCabe demonstrates this by using stream of consciousness as a narrative mode. I know what you’re saying. . .”I hate that! I hate Faulkner!” Well, McCabe isn’t Faulkner and his writing follows the pitter patter of an Irish lilt. Once you get the rhythm down, it’s a very enjoyable read. Macabre, but enjoyable, and there is nobody quite like the Irish who know how to use gallows humor to its fullest extent. Although, I will admit that I was familiar with McCabe’s writing style after reading Breakfast on Pluto last year. Also, after finishing this I immediately watched the film version of the novel directed by Neil Jordan. It was an absolute riot!

12. Tears of the Trufflepig by Fernando A. Flores: Reading this was like how I imagine a peyote fueled fever dream would be like. Noir, psychedelic, western, science fiction. . . it fits into so many genres that I wouldn’t know where to put it. Set in a not-too-distant future in South Texas where there are now three border walls, drugs have been made legal, and the new “rich” cartel commodity has maneuvered over to the food industry where animals are artificially grown for black market feasts, because natural crops have become scarce. Some of these animals were bio-engineered back from extinction, and others are the mythical made real like the titular “Truffepig”. However, artifacts of ancient civilizations are still in high demand for “collectors”. Flores created a fictional tribe of the Aranaña (the Trufflepig is part of their myth), and their shrunken heads are a hot item (enough to force people to kill, shrink, and lie about the origins of said heads who aren’t as ancient as one would like to believe), as well as the Olmec heads of Mesoamerica. While this novel is certainly a wild, enjoyable rollercoaster of storytelling, you have to admit that no one has quite touched on the topics of colonialism, imperialism, and the importance of learning about and respecting the customs and heritage of other people quite like Flores has.

13. Pachinko by Min Jin Lee: A saga encompassing nearly a century of generations in a Korean family. Before reading this I had no idea about the systemic racism towards Korean immigrants in Japan. We follow the Baek family from a small fishing village in Korea, to Japan during the second world war, to education in America, and finally to the Pachinko parlors of the underground back in Japan. Lee expertly uses the Baek Family to fool you with an illusion of progress for Korean immigrants in Japanese society, and touches on themes of sexual inequality, female beauty, alienation, cultural identity, and guilt. Even if you’re not interested in historical fiction, this is a great introduction to the geopolitical mess that was created in 1910 when Korea was annexed by Japan. You learn something, and you get to read a sweeping, enlightening, and heart rending family history while you’re at it.

14. The Country Girls Trilogy by Edna O’Brien: Downright charming! Each and every one of them. The first book is set primarily in the rural west of Ireland and features two young ladies, naïve yet likable Caithleen and her self-centered “best” friend Baba. Throughout the trilogy we follow the girls from primary school, to the convent, to Dublin in their single years, and finally London in their later, married lives. Their stories are filled with hilarity, heartbreak, familial falling out, and the terrors of becoming and being a woman. Banned in Ireland when it was published in the 1960s for its sexual imagery, and portrayal of women who desire, it was even burned in the author’s hometown. Also, reading this in 2020 made me realize how far we haven’t come in breaking down society’s antiquated expectations of girls. We’ve made some progress, but we’ve still got a ways to go!

15. Typhoid Mary: An Urban Historical by Anthony Bourdain: I miss Tony Bourdain something fierce, and this is probably one of his most overlooked books. As you can see in the links above, it’s currently selling for a pretty penny, and you can’t find anything but a used copy. (Boy, am I glad I grabbed a cheaper copy a few years ago!) Mary Mallon was an Irish immigrant who was a good cook. This allowed her to work in the kitchens of many affluent New Yorkers in the early 1900’s. There was one problem though. . . she was an asymptomatic carrier of Typhoid fever. With the handwashing and heat in the kitchens, how could she have spread the disease so easily, you ask? Well, handwashing wasn’t what it is today, and one of her most famous desserts was peach ice cream. No heat required. While there are plenty of books on Typhoid Mary, Bourdain takes a different approach to her story in a way that fans of his television shows are familiar with. He helps to humanize her, and break down her troubling mythic status, through his culinary expertise in ways that those of us in the current world climate can understand. He writes of Mary Mallon’s plight, “I’m a chef, and what interests me is the story of a proud cook — a reasonably capable one by all accounts — who at the outset, at least, found herself utterly screwed by the forces she neither understood nor had the ability to control. I’m interested in a tormented loner, a woman in a male world, in hostile territory, frequently on the run.” Mary Mallon was a lowly Irish immigrant trying to navigate a new country, asymptomatic carriers were something completely new and nearly incomprehensible to consider in the 1900’s, she was also a lone woman, and a victim of captivity in the name of public health. While we’re in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, this seemed like the perfect book to read in 2020. It certainly makes you fully understand that wearing a mask to protect you and others from spreading a virus is small potatoes in comparison to being forcibly quarantined for three decades. We have it easy. . .

You’ll notice that I’ve stopped linking to Amazon pages for the books listed above. Instead, you will find links to bookshop.org pages. This is an ecommerce start up that has made it their mission to give independent bookstores a fighting chance in this ever increasing online world of bookshopping that Amazon has dominated for so long. I am not sponsored by them. I don’t get any money for writing this silly little book blog, but I am a girl who loves her independent bookstores. So, if you’re looking to buy a new book via the interwebs, please check them out. You can even search for an indie store to support, and they will receive the full profit off of your order!

Check out 2019’s “Best of” list by clicking here.

Want to know what else I read in 2020 that didn’t make this list?

Click here to access my Goodreads profile.

[…] were in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, this seemed like the perfect book to read in 2020, and even made it onto my “Best of . . .” list. It certainly makes you fully understand that wearing a mask, and getting a vaccine to protect you […]

LikeLike

[…] Check out 2020’s “Best of” list by clicking here. […]

LikeLike

[…] Check out 2021’s “Best of” list by clicking here. […]

LikeLike